Several years ago I had an extended piece on this website about the various interpretations of The Wizard of Oz and I’ll be revisiting those topics throughout the year (and beyond). Not only is this year is the 75th anniversary of the release of the MGM classic film The Wizard of Oz (1939), but also the 50th anniversary of Henry Littlefield’s article suggesting that The Wizard of Oz was a “Parable on Populism,” a rural political movement in the late-19th century. in the Spring, 1964, issue of American Quarterly, Littlefield, a high school history teacher in upstate New York, asserted that L. Frank Baum had written The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

(1900) as a political allegory in which the characters represented various aspects of the 1896 election, when the Populist movement mounted a serious challenge to the two major parties in American politics. Over the years Littlefield’s interpretation of The Wizard of Oz has drawn considerable comment, much of which has centered on whether or not L. Frank Baum intentionally wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as some sort of political commentary, and this meme has now taken on a life of its own.

In my experience teaching American history I have found Littlefield’s interpretation of The Wizard of Oz to be a useful teaching tool, making a topic from the distant past much more lively and engaging for students. Littlefield explained that found that The Wizard of Oz was an effective means to teach his students about Populism and the 1896 election because the Baum’s imagery was so vivid and so easily attributable to the personalities and events of that period in history. Once Littlefield points out that the Scarecrow, representing Midwestern farmers, and the Tin Man, who embodies industrial workers, march on the Emerald City (Washington D.C.), after Dorothy kills the Wicked Witch of the East, who represents banks and industrial interests based on the East Coast, it’s easy to start looking for other references in The Wizard of Oz to the politics of its time.

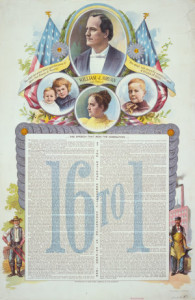

To understand Littlefield’s interpretation of The Wizard of Oz, it’s necessary to understand a little about Populism and the key issues of the 1896 election. The Populist Party grew out of the Farmers’ Alliances in the late-19th century. Farmers faced considerable economic hardship and they believed that monetary policy was determined by eastern bankers and industrial interests. The Farmers’ Alliances wanted greater government regulation of railroads, tax reform and the free coinage of silver to increase the money supply. The rapid growth of the Farmers’ Alliances and frustration with the two major parties led to the formation of the Populist party, which proved to be a serious challenge to the two major parties. In the election of 1892, James B. Weaver, the Populist candidate for President, received over 1,000,000 votes, and Populist congressional candidates received over 1,400,000 votes in the 1894 elections. The Populists enjoyed the greatest support on the Great Plains but they did not have much support among industrial workers, most of whom were in the east and Great Lakes regions. The Populists were faced with a choice of either running their own candidate for president in 1896 or casting their lot with the Democratic Party. The Populists chose “fusion” with the Democratic Party by nominating the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan, as their candidate.

Bryan embraced the issue of free coinage of silver in the 1896 campaign. In his acceptance speech at the Democratic national convention, Bryan claimed that farmers being unfairly burdened by a monetary policy that relied solely on the gold standard. With religious fervor he argued that farmers were being crucified on a “cross of gold.” For farmers to maintain their livelihood, Bryan argued that the money supply needed to be increased by concurrently employing the gold and silver standards, or “bi-metallism.” Bi-metallism was one of the main priorities of the Populists, but was not popular with industrial workers because it would cause inflation. Because of this, the Populists were not able to create a national movement. Bryan lost the election and the Populists would never again be a major force in American politics.

Though he never lived in Kansas, L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, had lived on the Great Plains, where Populism had the greatest influence. Henry Littlefield explained that Baum was not a political activist but he noted a number of events in Baum’s life that indicated an interest in Populist politics. According to Littlefield, “Baum created a children’s story with a symbolic allegory implicit within its story line and characterizations. The allegory always remains in a minor key, subordinated to the major theme and readily abandoned whenever it threatens to distort the appeal of the fantasy. But through it, in the form of a subtle parable, Baum delineated a Midwesterner’s vibrant and ironic portrait of this country as it entered the twentieth century.”

According to Littlefield, Dorothy is “Baum’s Miss Everyman.” Accompanying Dorothy on her journey down the yellow brick road are the Scarecrow and the Tin Man, which Littlefield noticed served as apt symbols for farmers and industrial workers. Baum’s Scarecrow is a response to the prejudicial notion that farmers were not smart enough to recognize their own interests, a sentiment expressed by William Allen White in his 1896 editorial “What’s the Matter with Kansas?” The Tin Man, dehumanized by factory labor, had rusted solid, symbolizing the closing of factories in the depression of 1893. The Cowardly Lion represents William Jennings Bryan, who was the Democratic nominee for president in 1896 and was also endorsed by the Populist Party. When the Cowardly Lion first meets Dorothy and her companions, he strikes the Tin Man but does not make a dent in his metal body. Littlefield equates the Cowardly Lion’s futile act with Bryan’s failure to win the vote of industrial labor.

Together the group journeys to Oz, which symbolizes Washington DC, to visit the great Wizard of Oz, symbolizing the president. Their trek is reminiscent of a march on Washington DC that occurred in the winter of 1893-1894. A populist named Jacob Coxey organized a small group of unemployed workers to march on the national capital in en effort to convince the government to put more money in circulation and to use those funds for public works programs to put people back to work. “Coxey’s Army” was modest in size and easily put down, but it did a number of similar such protests and brought the plight of the unemployed to national attention.

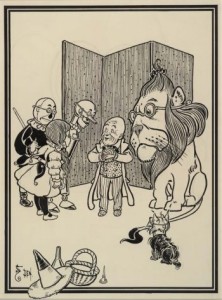

The 1939 MGM film made a number of changes to Baum’s original story. In Baum’s book the Emerald City isn’t green at all but a bland white. People are required to wear green glasses upon entry to give the city the illusion of being emerald colored. Also, when the group visit the Wizard of Oz, be appears to Dorothy as a giant head, to the Scarecrow as a gossamer fairy, to the Tin Man as a beast and to the Cowardly Lion as a ball of fire, just as a politician tries to be all things to all people. These changes blunt the cynicism about the self-serving nature of politicians in the original story. In order to get what they desire, the Wizard of Oz tells them to kill the Wicked Witch of the West, who represents the destructive forces of nature according to Littlefield. Dorothy kills the Wicked Witch by dousing her with a bucket of water, symbolizing the end of the drought that had been plaguing the West in the 1890s. When Dorothy and her friends return to the Wizard of Oz with the broom of the Wicked Witch of the West, he is exposed as a fraud. “The fearsome Wizard turns out to be nothing more than a common man, capable of shrews but mundane answers to these self-induced needs. Like any good politician he gives the people what they want.” The Wizard of Oz manages to provide everyone in the group something to satisfy their desire. Everyone except Dorothy, that is, because her goal of returning to Kansas, which Baum describes as dull and gray, is selfless.

Another change that the 1939 film made to Baum’s original story was that in the book, Dorothy wore silver shoes rather than ruby slippers. MGM wanted to highlight the Technicolor cinematography and changed the color of Dorothy’s shoes. Ruby slippers may have been a more appropriate choice for the film, but the imagery that Littlefield suggested was lost. The silver shoes, with the magical powers to solve Dorothy’s dilemma, symbolize the silver standard, just as the Populists believed that free silver would solve the problems facing farmers. But like many people, however, Dorothy does not understand the magical power she possesses. Instead she sets out on the yellow brick road, symbolizing the gold standard, which proves to be a perilous journey. She finally learns of their power at the end of the story, but the shoes are lost when Dorothy returns home. With the decline of the Populist Party, the free coinage of silver also faded as a national issue.

In part 2 of “The Wizard of Oz as a Parable on Populism” I’ll look at the critical reaction to Littlefield’s hypothesis and denials of Baum’s intent to write a political satire by his biographers.